Publications

Structural absorption by barbule micro-structures of super black bird of paradise…

Nature Communications 9:1 (2018)

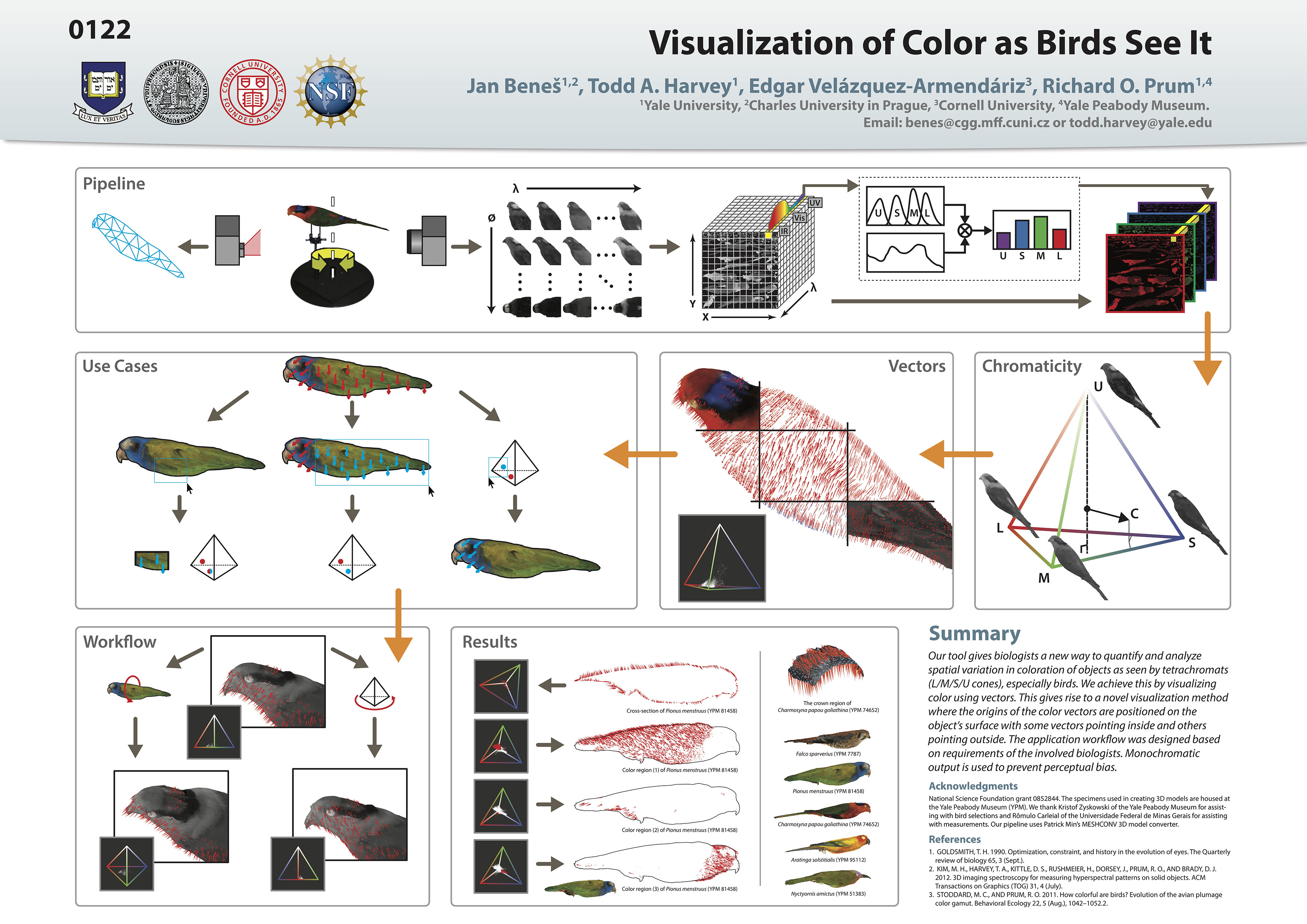

Visualization of color as birds see it

SIGGRAPH Asia (2013)

Measuring Spatially- and Directionally-varying Light Scattering from Biological...

Journal of Visualized Experiments 75 (2013)

Directional reflectance and milli-scale feather morphology of the African…

Journal of the Royal Society Interface 10:86 (2013)

Theses

Spatially- and Directionally-varying Reflectance of Milli-scale Feather…

Cornell University Ph.D. dissertation, August 2012

From Organismal- to Millimeter-scale: Methodologies for Studying Patterns in the…

Three Dimensional Imaging session • June 15, 2012

SPNHC 2012

Feather Reflectance: Directional Scattering and Iridescence

Cornell University M.S. thesis, August 2010 (unpublished selections)

Structural absorption by barbule microstructures of super black bird of paradise feathers

Press Coverage:

Scientific American: Back to Black: How Birds-of-Paradise Get Their Midnight Feathers

Audubon: Birds-of-Paradise Have Feathers That Act Like Black Holes

Science: ‘Superblack’ bird of paradise feathers absorb 99.95% of light

Wired: The World’s Most Metal Bird Makes Darkness Out of Chaos

Gizmodo: These Birds Evolved Feathers So Dark, They’re Like a ‘Black Hole’

Inside Science: BRIEF: For Birds of Paradise, Super-Black Feathers Make Bright Spots Shine

Smithsonian: Scientists Shine New Light on the Blackest Black Feathers

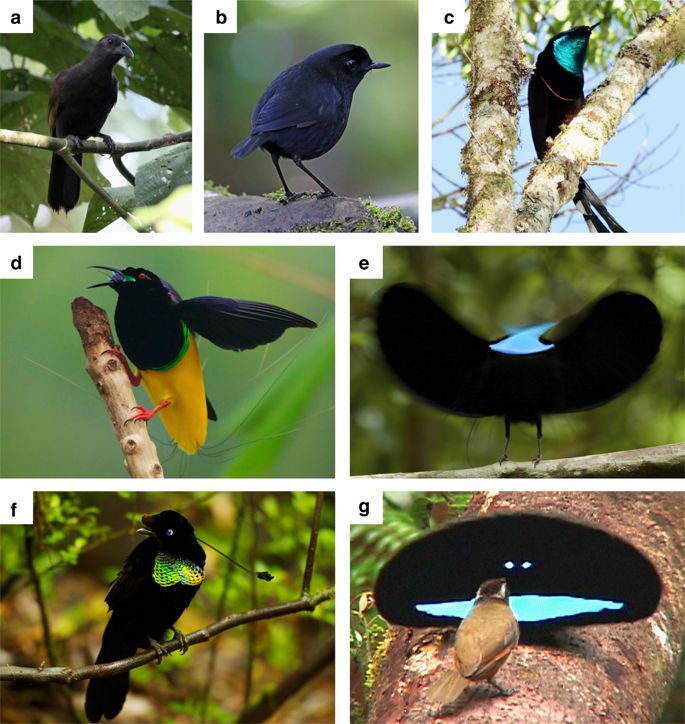

Six species of birds of paradise and one close relative…More

Six species of birds of paradise and one close relative. a,b Species with normal black plumage patches. c–g Species with super black plumagepatches. a Paradise-crow (Lycocorax pyrrhopterus). b Lesser Melampitta (Melampitta lugubris), a Papuan corvoid closely related to birds of paradise. c Princess Stephanie’s Astrapia (Astrapia stephaniae). d Twelve-wired Birds-of-Paradise (Seleucidis melanoleucus). e Paradise Riflebird (Ptiloris paradiseus during courtship display). f Wahnes’ Parotia (Parotia wahnesi). g Superb Bird-of-Paradise (Lophorina superba) during courtship display with female (brown plumage). Photocredits: a @Hanom Bashari/Burung Indonesia; b Daniel López-Velasco; c Trans Niugini Tours; d–f Tim Laman; g Ed Scholes.

Examples of normal and super black feather microstructure…More

Examples of normal and super black feather microstructure. a SEM micrograph of Lycocorax pyrrhopterus normal black feather with typical barbule morphology; scale bar, 200 µm. b SEM micrograph of Parotia wahnesi super black feather with modified barbule arrays; scale bar, 50 µm. c Gold sputter-coated normal black breast feather of Melampitta lugubris appears gold. d Gold sputter-coated super black breast feather of Ptiloris paradiseus retains a black appearance indicating structural absorption. SEM stubs are 12.8 mm in diameter.

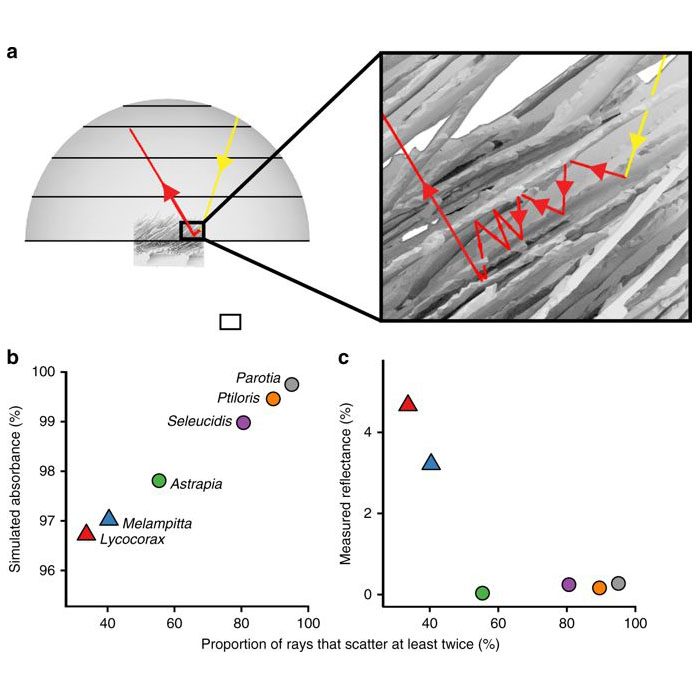

Ray-tracing simulations. a Simulation from FRED…More

Ray-tracing simulations. a Simulation from FRED showing the trace of a ray that scatters multiple times between barbules of a super black feather. b Substantial variation in frequency of multiple scattering events among species predicts variation in structural absorption. c Measured reflectance is significantly negatively correlated with the proportion of reflected rays that scattered at least twice (linear regression: R2 = 0.68, slope = −0.063, SE = 0.021, and P < 0.05)

Abstract

Many studies have shown how pigments and internal nanostructures generate color in nature. External surface structures can also influence appearance, such as by causing multiple scattering of light (structural absorption) to produce a velvety, super black appearance. Here we show that feathers from five species of birds of paradise (Aves: Paradisaeidae) structurally absorb incident light to produce extremely low-reflectance, super black plumages. Directional reflectance of these feathers (0.05–0.31%) approaches that of man-made ultra-absorbent materials. SEM, nano-CT, and ray-tracing simulations show that super black feathers have titled arrays of highly modified barbules, which cause more multiple scattering, resulting in more structural absorption, than normal black feathers. Super black feathers have an extreme directional reflectance bias and appear darkest when viewed from the distal direction. We hypothesize that structurally absorbing, super black plumage evolved through sensory bias to enhance the perceived brilliance of adjacent color patches during courtship display.

Acknowledgements

Xianghui Xiao and the 2-BM beamline group provided assistance with CT scanning and analysis at the APS facility, Argonne National Lab. Jeremiah Trimble and Kate Eldridge assisted with collections usage…More. The research has been improved by discussions with David Brainard, David Shoehalter, Kristof Zyskowski, David Haig, James Harvey, Ryan Irvin, and members of the Prum Lab. Ed Scholes, Tim Laman, Trans Niugini Tours, Hanom Bashari, and Daniel López kindly gave permission to reproduce photos of birds of paradise (Fig. 1). Andrew Farris assisted with kermal regressions for the directional reflectance plots. This research was funded by the W. R. Coe Fund of Yale University, by a Sigma XI student research fellowship to D.E.M., and by a Mind, Brain, and Behavior Graduate Student Award to D.E.M. D.E.M. was supported by the Department of Defense (DoD) through the National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship (NDSEG) Program. D.E.M. was also supported by a Theodore H. Ashford Graduate Fellowship in the Sciences. Tomography data collections at the Advanced Photon Source beamline 2-BM, Argonne National Laboratory were supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science (Proposal ID 41887). T.J.F. was supported by a NSF Postdoctoral Fellowship in Biology (#1523857). Richard Pfisterer of Photon Engineering graciously licensed FRED to T.A.H. for this research. This work was performed in part at the Harvard University Center for Nanoscale Systems (CNS), a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Network (NNCI), which is supported by the National Science Foundation under NSF ECCS award no. 1541959.

Less

Press Coverage:

Scientific American: Back to Black: How Birds-of-Paradise Get Their Midnight Feathers

Audubon: Birds-of-Paradise Have Feathers That Act Like Black Holes

Science: ‘Superblack’ bird of paradise feathers absorb 99.95% of light

Wired: The World’s Most Metal Bird Makes Darkness Out of Chaos

Gizmodo: These Birds Evolved Feathers So Dark, They’re Like a ‘Black Hole’

Inside Science: BRIEF: For Birds of Paradise, Super-Black Feathers Make Bright Spots Shine

Smithsonian: Scientists Shine New Light on the Blackest Black Feathers

Leveraging Diverse Specimen types to Integrate Behavior and Morphology

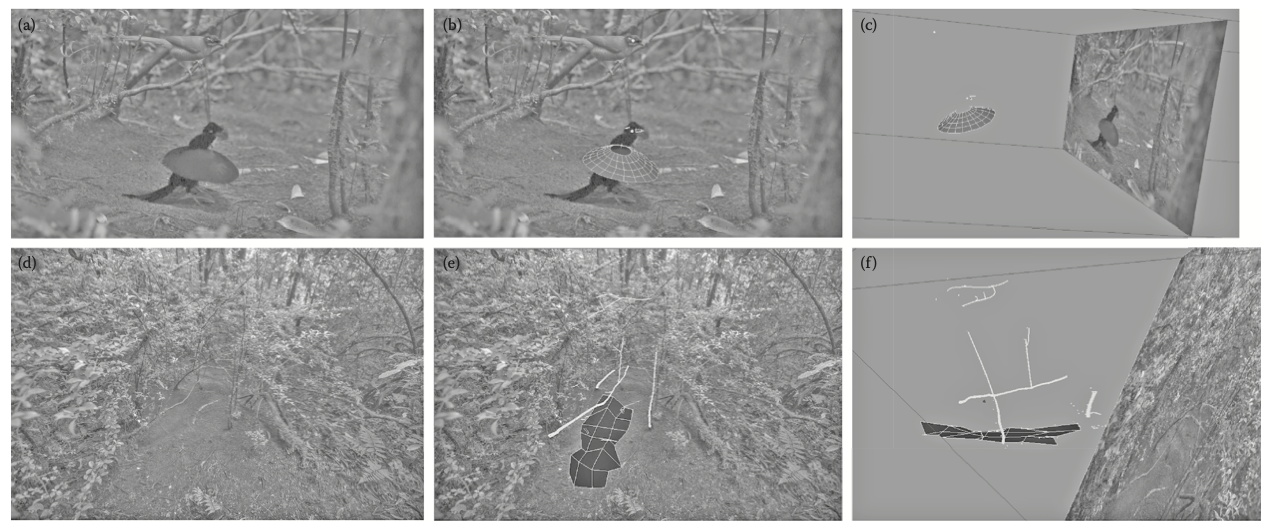

Real and virtual male and court of Parotia wahnesi. (a) A single video frame showing the ballerina dance…More

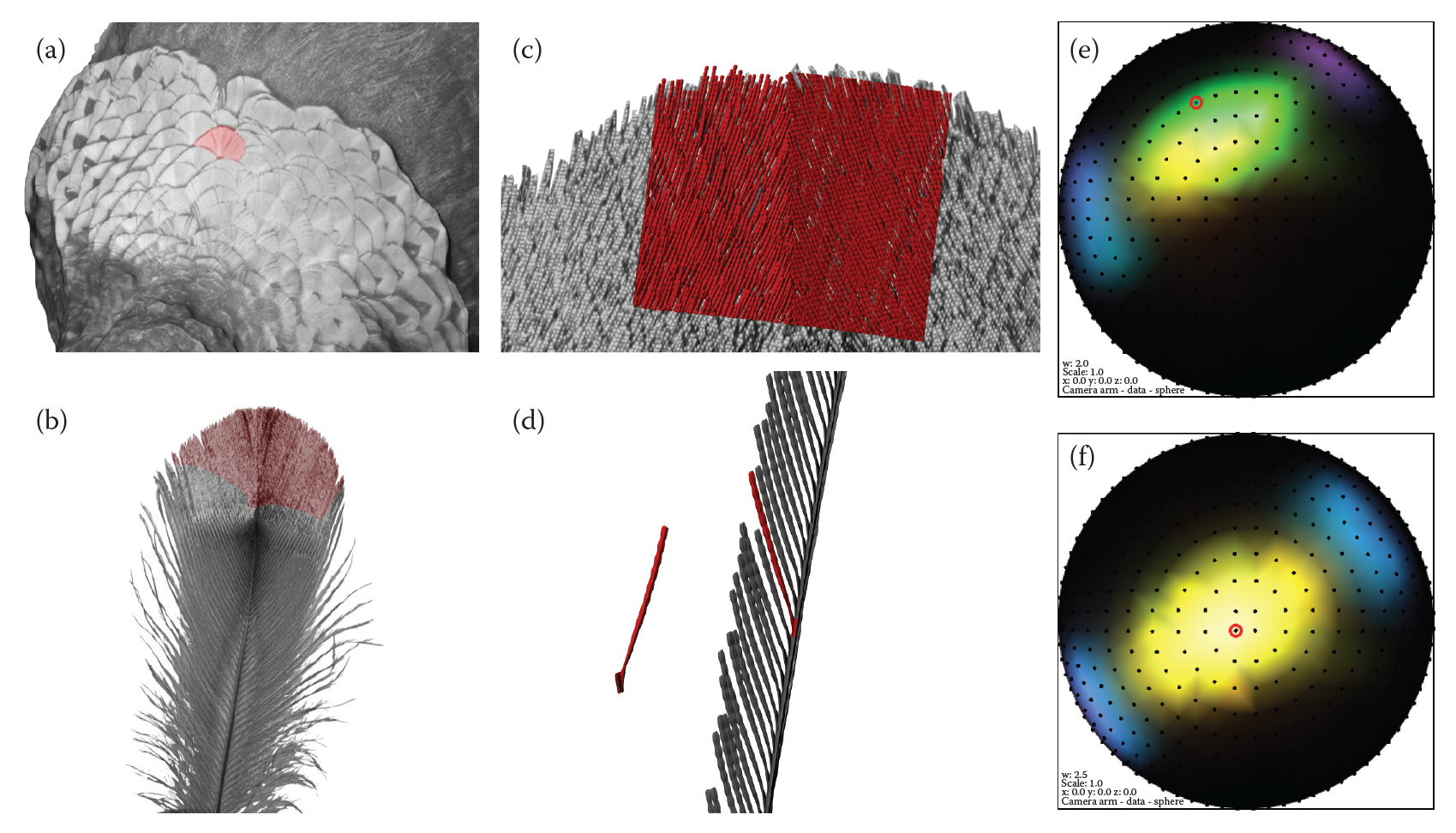

Examples of feather imaging from P. wahnesi round skin specimen showing morphological…More

Abstract

Biological specimens can hold a surprising wealth of information, and different specimen types hold different, but complementary, sets of data. This is true not only of physical specimens, such as study skins and skeletal preparations, but also of media “specimens,” such as an audio recording of an animal’s voice, a video of its display, or a photograph of its nest. When diverse specimen types are taken from the same species (species-level vouchering) and especially the same individual (individual-level vouchering), they can be leveraged to extract ever more complete insights into evolution, ecology, behavior, and functional morphology. In this chapter, we present two case studies that combine data obtained from analyses of both physical and media specimens. These case studies illustrate the diverse approaches undertaken using diverse specimen resources, approaches that allow us to address challenging questions and explore new areas of inquiry. Modern collecting techniques, such as behavioral vouchering using high-speed video and audio recordings, and advanced digital techniques, including several types of anatomical, acoustic, and optical analyses, were applied to extract information from specimens that previously would have been impossible to obtain. Results include surprising behavioral, functional, and evolutionary insights into two fascinating groups of birds: the manakins (Pipridae) and the birds-of-paradise (Paradisaeidae). Similar approaches can be employed to gain insights into other taxa. Importantly, these insights were only possible through an integrated approach that combined information gleaned from multiple specimen types, thereby highlighting the complementary nature of diverse specimen types.

Acknowledgements

All authors are, of course, indebted to the many museums from which they have borrowed specimens, and consequently to the individual collectors who work to make these collections possible. Most critical, the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, the Peabody Museum…More, the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates, the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, the Louisiana State University Museum of Natural History, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds supported these various research projects with unique specimens.

For the Parotia research, all digital specimens are archived in the Macaulay Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. CT data of Parotia feathers were collected and processed with the help of X. Xiao and D. Gursoy at beam line 2-BM of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Labs, and supported under proposal 39343. The Richard O. Prum Lab at Yale University provided CT computing resources. D. Milewicz of Yale University segmented Parotia CT data. S. Marschner of Cornell University provided access to his lab for imaging the Parotia specimen required for computing directional light scattering and photogrammetric surface reconstructions. D. Young produced 3D surface models of the specimen and its environment.

Less

Visualization of color as birds see it

Downloads:

Abstract

Our objective is to provide ornithologists with a tool for looking at 3D models of birds through the eyes of other birds. This tool overcomes the limits of the human visual system to allow scientists to quantify and analyze avian color in a completely novel way.

Downloads

Acknowledgements

National Science foundation grant 0852844. The specimens used in creating 3D models are housed at the Yale Peabody Museum (YPM). We thank Kristof Zyskowski of the Yale Peabody Museum for assisting with bird selections and…More Rômulo Carleial of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais for assisting with measurements. Our pipeline uses Patrick Min’s MESHCONV 3D model converter.

Less

From microscopic feather structure to whole-organism display behavior: using multiple specimen types to uncover the private courtship signals of Parotia wahnesi (Paradiseidae)

Abstract

Characterizing the appearance and signaling performance of the courtship display of Parotia wahnesi is challenging due to its directional and temporal attributes. We used vouchered behavioral specimens in the form of field-generated video-recordings, in combination with reflectance measurements from a museum specimen in the lab to reconstruct the “anatomy” of the extended courtship phenotype of the male Parotia wahnesi. We investigated three fundamental components of its directional signaling: (1) the direction of light illuminating the male in his court, (2) the direction of the reflectance from the male’s iridescent ornamental plumage, and (3) the position and orientation of the ornaments with respect to the female during display. We show how plumages are tightly aligned at multiple structural scales to maximize the effectiveness of visual signals. In a highly choreographed performance, ornamental plumages entice females through contrasting shape, intensity, and color, while ancillary plumages construct a backdrop framing those ornaments. We present evidence that the male leverages the geometry of his court and lighting environment to gain additional directional advantages. Every attribute, whether intrinsic or extrinsic to the male himself, hones signal production to generate spectacular but private displays intended for visiting female birds, unobservable from other vantage points.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the University of Kansas Natural History Museum for access to their Parotia Wahnesi specimen.

Directional reflectance and milli-scale feather morphology of the African Emerald Cuckoo, Chrysococcyx cupreus

Press Coverage:

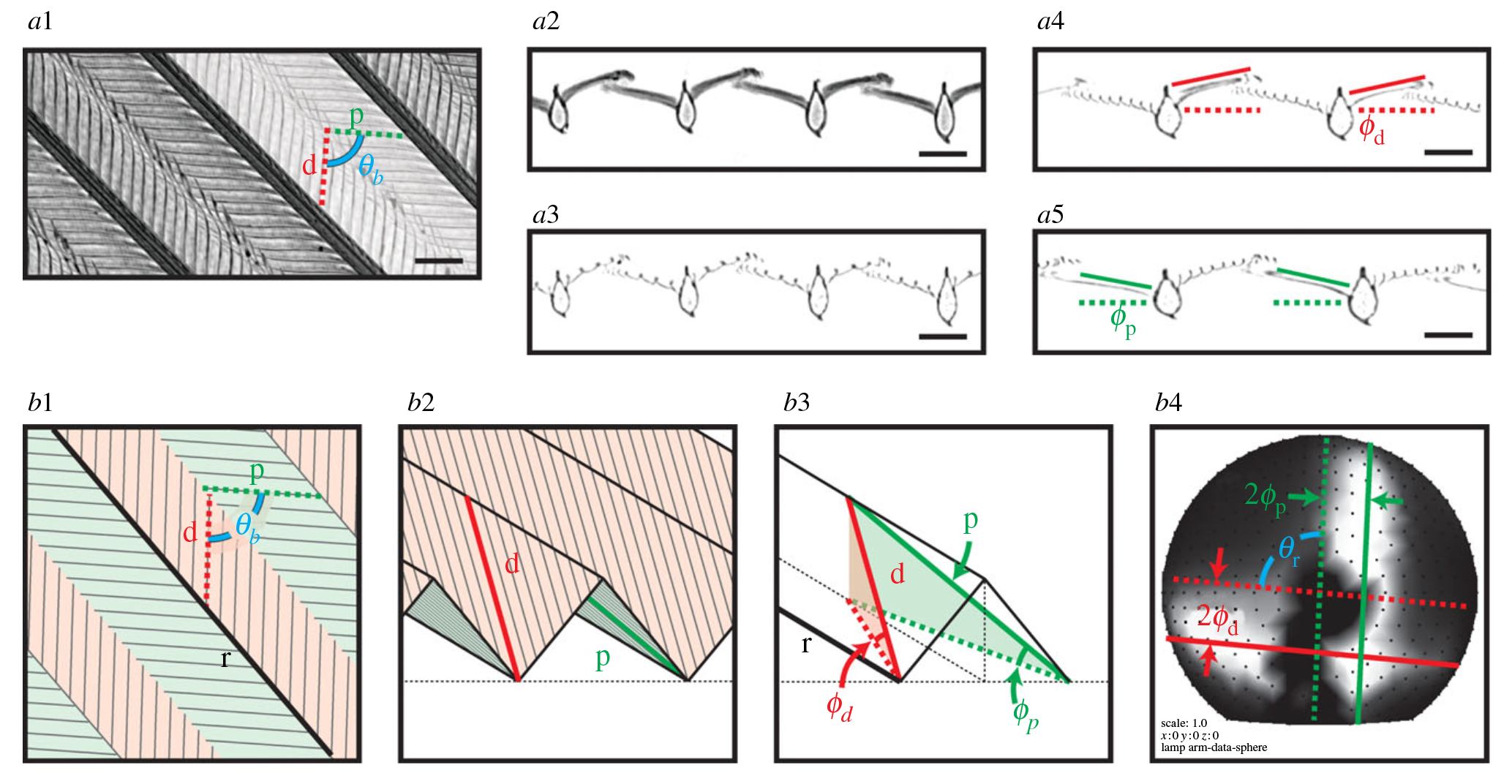

MicroCT images (a) and schematic diagrams (b) of the barb structure of the medial…More

MicroCT images (a) and schematic diagrams (b) of the barb structure of the medial vane. (r) Ramus. (d) Distal barbule. (p) Proximal barbule. (ɸd) Inclination angle of the base of the distal barbule. (ɸp) Inclination angle of the base of the proximal barbule. (𝜽b) Azimuth angle between bases of the distal and proximal barbules projected in the plane of the macro-surface. (𝜽r) Angle between the two planes fitted to the reflectance of the bases of the distal and proximal barbules. (a) MicroCT reconstructions: (a1) Obverse view oriented with rachis up and macro-surface in the plane of the page matches the gantry experimental setup. (a2, a3) Transverse cross sections of the rami. (a4) Longitudinal cross-sections of the base of the distal barbule in plane with the macro-surface normal. (a5) Longitudinal cross-sections of the base of the proximal barbule in plane with the macro-surface normal. A slab consists of multiple slices. Scale bar, 100 mm. (b) Schematic diagrams: (b1) Obverse view. (b2) Oblique transverse cross-section. (b3) Inclination of the bases of the distal and proximal barbules. (b3) Average directional reflectance of a rectangle region containing distal and proximal barbules.

Abstract

Diverse plumages have evolved among birds through complex morphological modifications. We investigate how the interplay of light with surface and subsurface feather morphology determines the direction of light propagation, an understudied aspect of avian visual signalling. We hypothesize that milli-scale modifications of feathers produce anisotropic reflectance, the direction of which may be predicted by the orientation of the milli-scale structure. The subject of this study is the African Emerald Cuckoo, Chrysococcyx cupreus, noted for its shimmering green iridescent appearance. Using a spherical gantry, we measured the change in the directional reflectance across the feather surface and over a hemisphere of incident lighting directions. Using a microCT scanner, we also studied the morphology of the structural branches of the barb. We tracked the changes in the directional reflectance to the orientation of the structural branches as observed in the CT data. We conclude that (i) the far-field signal of the feather consists of multiple specular components, each associated with a different structural branch and (ii) the direction of each specular component is correlated to the orientation of the corresponding structure.

Supplementary Material

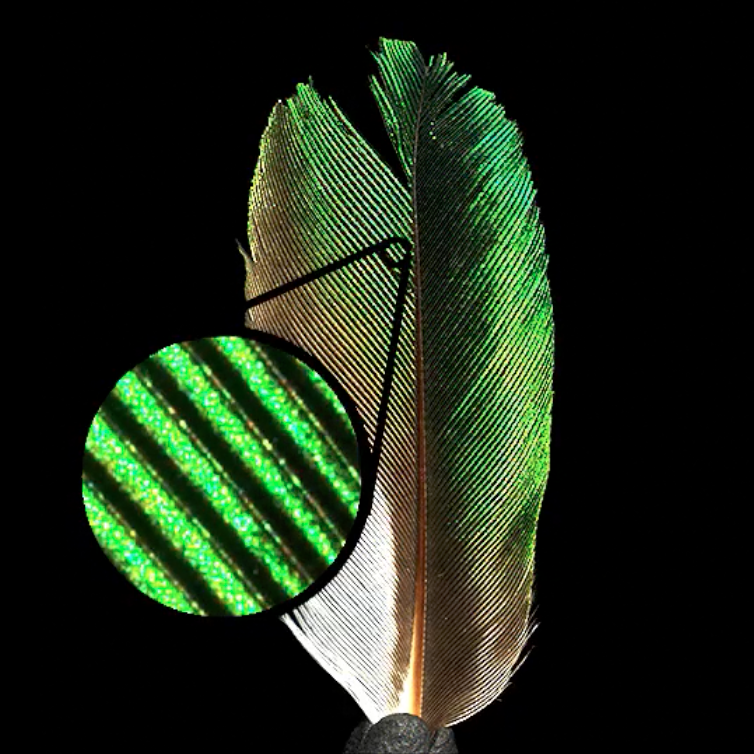

Anisotropic reflectance from the brilliant green plumage of Chrysococcyx cupreus…More

Anisotropic reflectance from the brilliant green plumage of Chrysococcyx cupreus (African Emerald Cuckoo), Male. Photographed by Dr. Hugh Chittenden in Eshowe, KwaZulu/Natal, South Africa on 4 Jan 2010 at 14h30. Copyright Dr. Hugh Chittenden. Reproduced with permission.

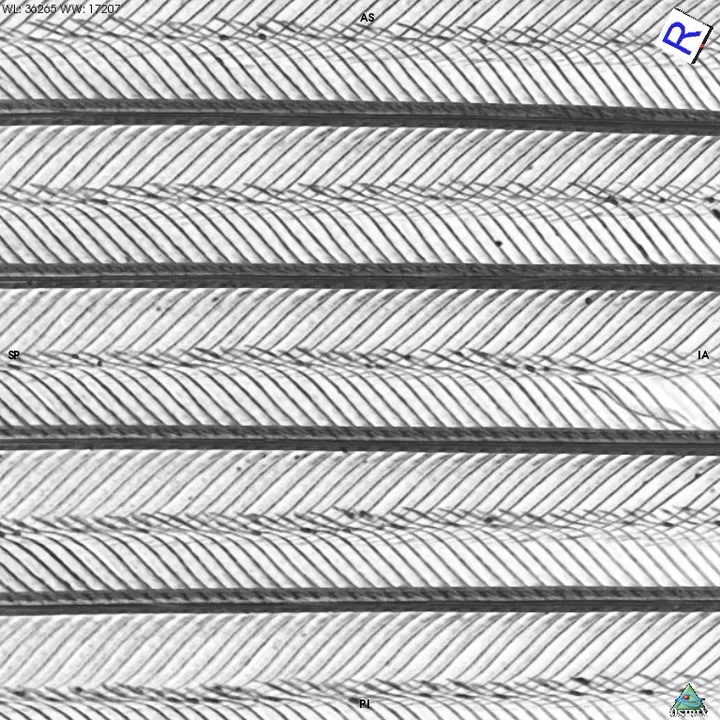

The microCT reconstruction of the Chrysococcyx cupreus (African Emerald Cuckoo)…More

The microCT reconstruction of the Chrysococcyx cupreus (African Emerald Cuckoo) tertial feather vane rotating around an axis in the plane of the vane and perpendicular to its rami. The inclined bases of the barbules form a three-dimensional herringbone zigzag in a plane orthogonal to the longitudinal axes of the rami. Our geometrical model correctly predicts the direction of the reflection from the orientation of the zigzagged structure.

Shimmering anisotropic reflectance from a male Chrysococcyx cupreus…More

Shimmering anisotropic reflectance from a male Chrysococcyx cupreus (African Emerald Cuckoo) tertial feather illuminated by a light source orbiting the feather. Throughout the movement the light maintains a 30 degree elevation towards the feather's tip (in a plane 30 degrees above the midline of the feather vane). The video begins with the light located at the right side of the screen and at a grazing angle to the feather. The light crosses in front of the feather as it moves towards the left side of the screen. Upon reaching the left side of the screen the light bounces back towards the right side and again towards the left before concluding midway. The zoom region shows the rami and distal barbules illuminated by the light. This particular light path does not illuminate the proximal barbules.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr Ellis Loew, Dr John Hermanson and Dr Susan Suarez, Cornell University; Dr James Harvey, CREOL, University of Central Florida; and Dr Richard Prum, Yale University for their guidance and review of this manuscript…More; Kalliope Stournaras, University Freiburg, for her translation of the Durrer and Villiger manuscript; Josh VanHouten, Yale University, and Mark Riccio, Cornell University, for microCT measurements; and Dr Donald Greenberg, Dr Jon Moon, Dr Jaroslav Krivanek, Wenzel Jakob, Edgar Velazquez-Armendariz and Hurf Sheldon, Cornell University, for their contributions in Computer Graphics. This research was supported by funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF CAREER award CCF-0347303 and NSF grant CCF-0541105).

Less

Press Coverage:

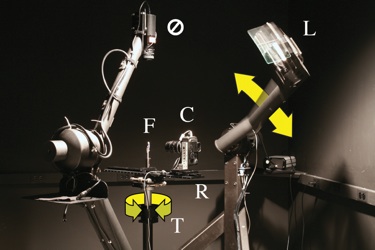

Measuring Spatially- and Directionally-varying Light Scattering from Biological Material

Abstract

Light interacts with an organism's integument on a variety of spatial scales. For example in an iridescent bird: nano-scale structures produce color; the milli-scale structure of barbs and barbules largely determines the directional pattern of reflected light; and through the macro-scale spatial structure of overlapping, curved feathers, these directional effects create the visual texture. Milli-scale and macro-scale effects determine where on the organism's body, and from what viewpoints and under what illumination, the iridescent colors are seen. Thus, the highly directional flash of brilliant color from the iridescent throat of a hummingbird is inadequately explained by its nano-scale structure alone and questions remain. From a given observation point, which milli-scale elements of the feather are oriented to reflect strongly? Do some species produce broader "windows" for observation of iridescence than others? These and similar questions may be asked about any organisms that have evolved a particular surface appearance for signaling, camouflage, or other reasons.

In order to study the directional patterns of light scattering from feathers, and their relationship to the bird's milli-scale morphology, we developed a protocol for measuring light scattered from biological materials using many high-resolution photographs taken with varying illumination and viewing directions. Since we measure scattered light as a function of direction, we can observe the characteristic features in the directional distribution of light scattered from that particular feather, and because barbs and barbules are resolved in our images, we can clearly attribute the directional features to these different milli-scale structures. Keeping the specimen intact preserves the gross-scale scattering behavior seen in nature. The method described here presents a generalized protocol for analyzing spatially- and directionally-varying light scattering from complex biological materials at multiple structural scales.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jaroslav Křivánek, Jon Moon, Edgar Velázquez-Armendáriz, Wenzel Jakob, James Harvey, Susan Suarez, Ellis Loew, and John Hermanson for their intellectual contributions…More. The Cornell Spherical Gantry was built from a design due to Duane Fulk, Marc Levoy, and Szymon Rusinkiewicz. This research was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF CAREER award CCF-0347303 and NSF grant CCF-0541105).

Less

3D Imaging Spectroscopy for Measuring Hyperspectral Patterns on Solid Objects

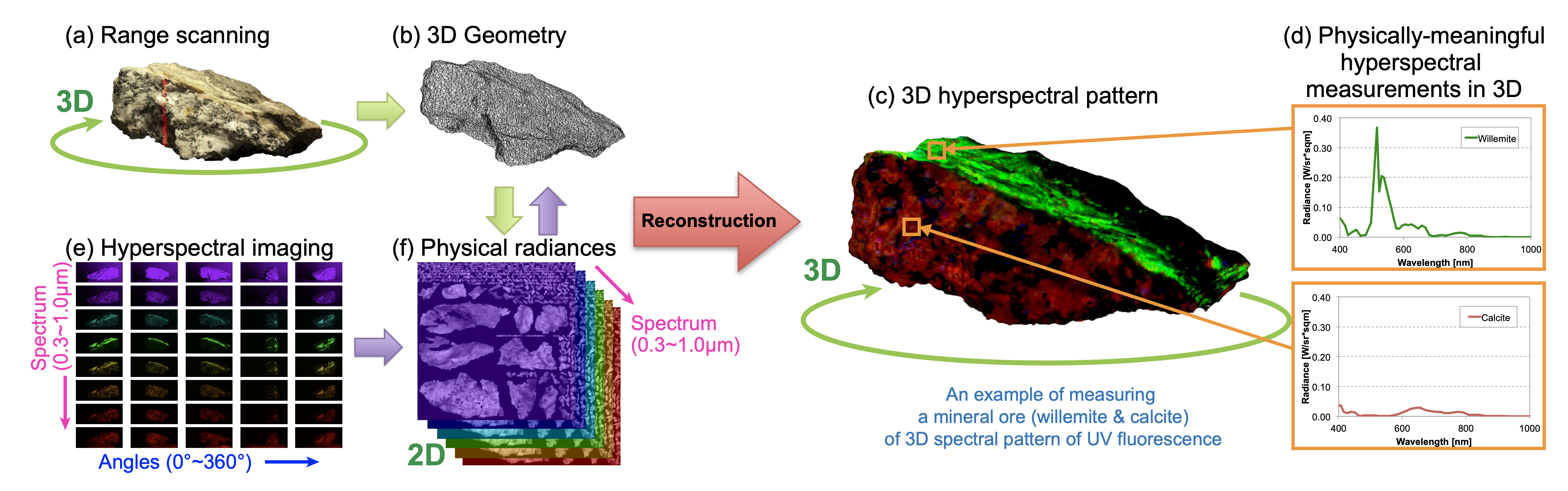

An overview of our system for measuring a three-dimensional (3D) hyperspectral pattern on a solid object. Our 3D imaging spectroscopy (3DIS) system measures 3D geometry…More

An overview of our system for measuring a three-dimensional (3D) hyperspectral pattern on a solid object. Our 3D imaging spectroscopy (3DIS) system measures 3D geometry and hyperspectral radiance simultaneously. Piecewise geometries and radiances are reconstructed into a 3D hyperspectral pattern by our reconstruction pipeline. Our system is used to measure physically-meaningful 3D hyperspectral patterns of various wavelengths for scientific research.

Abstract

Sophisticated methods for true spectral rendering have been developed in computer graphics to produce highly accurate images. In addition to traditional applications in visualizing appearance, such methods have potential applications in many areas of scientific study. In particular, we are motivated by the application of studying avian vision and appearance. An obstacle to using graphics in this application is the lack of reliable input data. We introduce an end-to-end measurement system for capturing spectral data on 3D objects. We present the modification of a recently developed hyperspectral imager to make it suitable for acquiring such data in a wide spectral range at high spectral and spatial resolution. We capture four megapixel images, with data at each pixel from the near-ultraviolet (359 nm) to near-infrared (1,003 nm) at 12 nm spectral resolution. We fully characterize the imaging system, and document its accuracy. This imager is integrated into a 3D scanning system to enable the measurement of the diffuse spectral reflectance and fluorescence of specimens. We demonstrate the use of this measurement system in the study of the interplay between the visual capabilities and appearance of birds. We show further the use of the system in gaining insight into artifacts from geology and cultural heritage.

Downloads

Supplementary Material

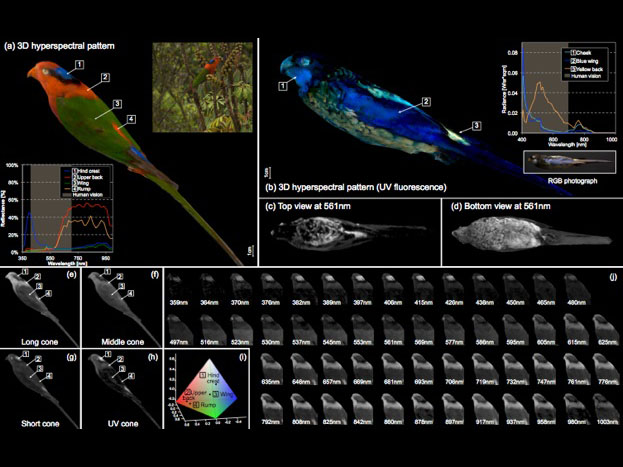

(a) Charmosyna papou goliathina, Papuan Lorikeet (Yale Peabody Museum: YPM41702): Hyperspectral…More

(a) Charmosyna papou goliathina, Papuan Lorikeet (Yale Peabody Museum: YPM41702): Hyperspectral reflectance and tetrachromatic color of the blue of the hind-crown, red of the upper back, green of the lower back, and red of the rump. Inset (top): simulation rendering of the bird in its natural environment. Inset (bottom): diffuse reflectance readings (359nm–1μm) on the 3D hyperspectral patterns as compared to human vision. (b)–(d) UV-induced visible-fluorescence of the plumage of Platycercus venustus, Northern Rosella (Yale Peabody Museum: YPM74652): yellow fluorescing contour feathers of the back and belly. Blue fluorescing wing feathers, and contour feathers of the crown and cheek. Inset: radiant emission readings of UV-induced fluorescence. (e)–(h) Each represents the photon catch on C. papou goliathina of one of the tetrachromatic cones: U, S, M, and L. (i) Three-dimensional chromaticity representation of the plumage of the bird in the USML tetrahedron color space [Stoddard and Prum 2008]. (j) The entire hyperspectral patterns of the bird in 3D. Refer to the supplementary video for visualizations of full 3D spectrum.

Supplemental Video

Acknowledgements

We are especially grateful to Patrick Paczkowski – for his tremendous efforts in support of the entire process of producing this publication – and Hongzhi Wu, Bing Wang, Kristof Zyskowski, Stefan Nicolescu, Roger Colten, Catherine Sease, Jacob Berv, Tim Laman…More, Edgar Velazquez-Armendariz, and Jennifer Helvey for their assistance. In addition, we thank the reviewers for their valuable comments. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grants NSF-0852844, NSF-0852843, and NSF-1064412).

Less

From Organismal- to Millimeter-scale: Methodologies for Studying Patterns in the Color and Direction of the Reflectance from Avian Organisms

Abstract

Avian organisms have evolved plumage of astounding beauty and diversity, including brilliant color and dramatic pattern. Plumage is fundamental to how birds interact with their world; the signaling function of plumage plays a role in an organism’s social interaction and is a determining factor in a organism’s overall visual identity. The organization of modified plumage structure over the surface of the bird produces dramatic variation in appearance both within and between species. Previous case studies have established the vast morphological modifications of individual, specialized feathers, their placement on the body, and the millimeter-scale topography generated by the shape and orientation of feather sub-structures. We study plumage morphology and reflectance to explain its potential function in avian behavior, its development and evolution. We propose that a change in the form and orientation of a feather, and in turn its sub-structures, changes its interaction with light and thus alters appearance. We began our investigations by asking: for every specific component of the modified structure, is there a corresponding signal function and can we identify and measure the signal? In this talk we will discuss two systems of non-destructive tools and techniques we have developed to study and measure plumage morphology and its reflectance from the organismal- to millimeter-scale; the first captures images with high spatial and high spectral resolution and corresponding organismal-scale geometries, while the second obtains high spatial and high directional resolution and millimeter-scale geometries. We will show how plumage morphology at different structural scales influences change in the spectral and directional components of the reflectance over the surface of the organism. We will also suggest the research and archival potential of the large digital data sets acquired in the course of our studies.

Acknowledgements

Cornell Project: Dr. Steve Marschner, Dr. Ellis Loew; Mark Riccio, Cornell MicroCT Facility; Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates; Dr. Don Greenberg, Dr. Jaroslav Krivanek, Dr. Jon Moon, Edgar Velazquez-Armendariz, and Wenzel Jakob. Kalliope Stournaras (University Freiburg).

Yale Project: Dr. Richard Prum, Dr. Holly Rushmeier, Dr. Min Kim; Patrick Paczkowski; Dr. Kristof Zyskowski, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History; also Teresa Feo, Jacob Musser.

Spatially- and Directionally-varying Reflectance of Milli-scale Feather Morphology

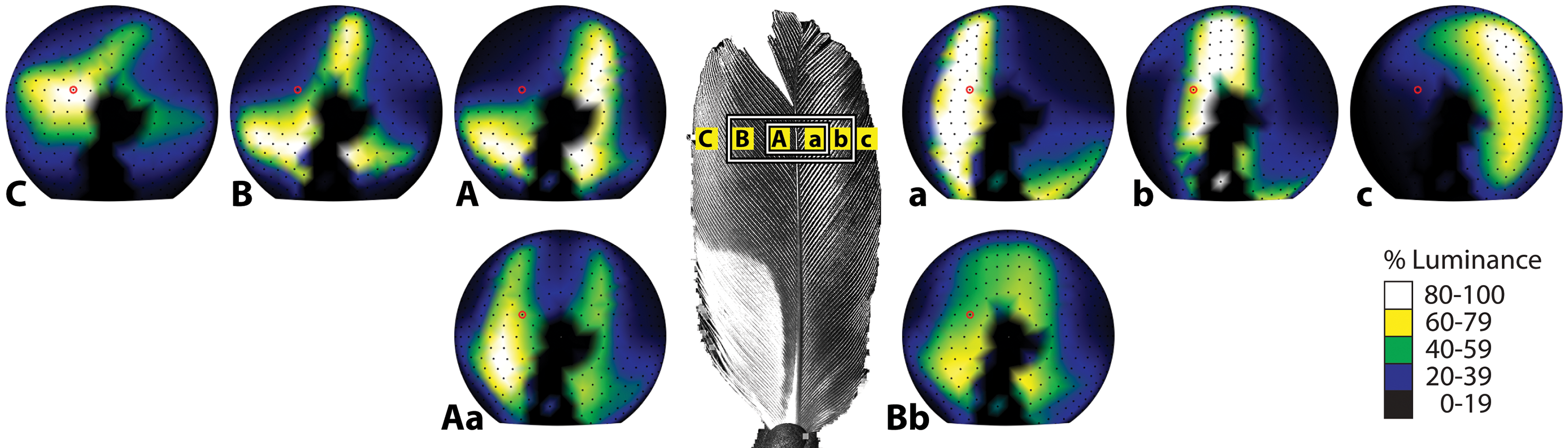

Average directional reflectance of rectangular regions of Chrysococcyx cupreus…More

Average directional reflectance of rectangular regions of Chrysococcyx cupreus: (A–C) 3 regions of the medial vane, (a–c) 3 regions of the lateral vane, and (Aa & Bb) 2 regions spanning both vanes. Luminance plotted in direction cosine space.

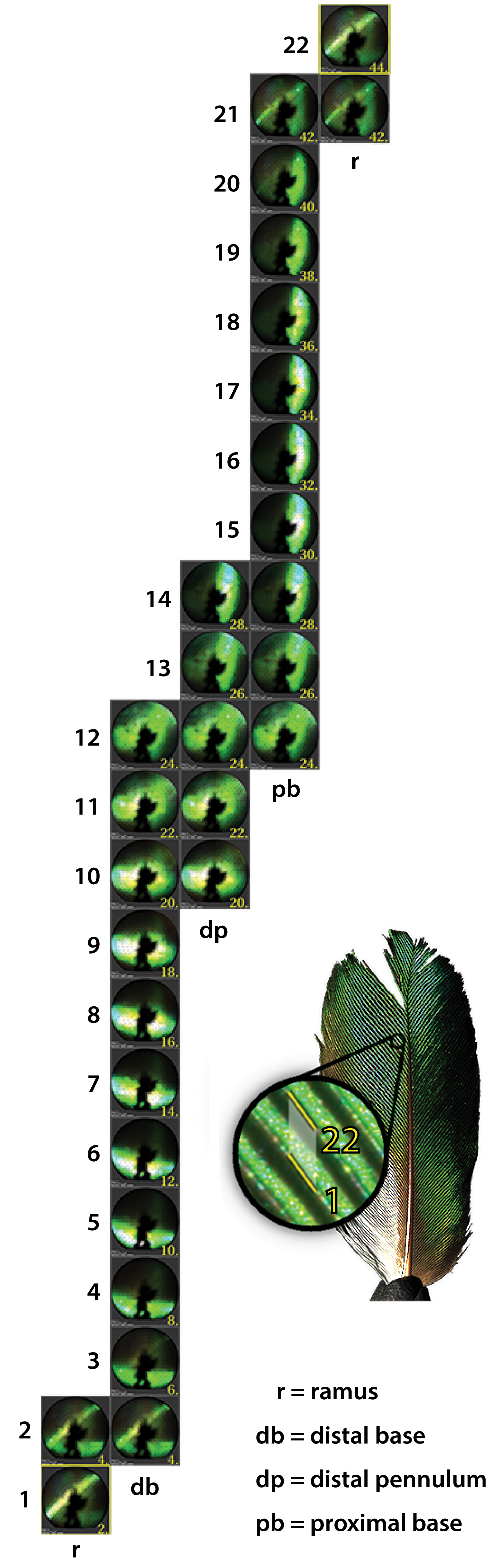

RGB directional reflectance of a region between 2 barbs of the medial vane was subdivided…More

Special Committee

Dr. Susan Suarez, Dr. Steve Marschner, Dr. Kim Bostwick, Dr. Ellis Loew, and Dr. John Hermanson

Abstract

Birds have evolved diverse plumage through sophisticated morphological modifications. The interaction of light with these modifications alters the reflectance from feathers, producing complex and directionally-variable visual signals. I hypothesize that structural modifications of the feather produce anisotropic reflectance, the direction of which is determined by the orientation of the structure of the vane.

Variation in reflectance originates from the interplay of light with two classes of feather structure: its surface and subsurface volume. Different structural scales within the two structural classes influence light scattering within the UV-visible spectrum. The overall shape and surface of the feather vane (the macro-scale) and of its component members (the milli-scale) scatter light according to principles of geometric optics. Subsurface nano-scale structure in many feathers generate so-called “structural coloration,” which is a purely physical optics phenomenon and can differ drastically from ordinary coloration mechanisms such as pigmentation. Iridescence, from which many feathers derive their vivid, eye-catching changeable color, is one type of structural color that varies as a function of viewing angle.

This thesis presents investigations into a previously understudied aspect of avian visual signaling: directional reflectance and its relationship to milli-scale structure. Having observed that the stratified nano-scale morphology of structurally-colored plumage contours the milli-scale cortex of the vane, I determined that measurements of the milli-scale could be substituted for a more complex study of directional reflectance from the nano-scale. I thereby hypothesize that the direction of the reflectance from a vaned feather can be predicted from the orientation of its milli-scale morphology—its barbs and barbules. In collaboration with my colleagues at Cornell University, I developed non-destructive tools and methods to investigate the signaling potential of the feather. I correlate measurements of directional light scattering to the milli-scale morphology of select samples of structurally-colored bird plumage. The results of these analyses lead to a more thorough understanding of the relationships between directional reflectance and the structure of the feather itself. Having found the reflectance to be anisotropic, I demonstrate that the change in the direction of the reflectance over the surface of the vane can in fact be predicted from the orientation of the different branches of the barb. The improved understanding of the variation in directional reflectance over the surface of the feather, a phenotypic component, should allow for better comprehension of avian behavior, evolution of morphological adaptations, and the synthesis of more accurate predictive models.

RGB directional reflectance of a region between 2 barbs of the medial vane was subdivided…More

RGB directional reflectance of a region between 2 barbs of the medial vane was subdivided into 44 linear divisions. The Average reflectance of 22 subsampled divisions is shown: (1) of line 1 along a length of ramus; (2–21) along sequential lines following step-wise movements; (22) of line 22 along a length of the adjacent ramus.